At just 19 years old John Drummond was granted a short service commission by the RAF on 4 June 1938. Less than two and a half years later he was dead, having given his life defending his country from the threat of invasion.

He saw service in Norway for which he was awarded a DFC before transferring to Biggin Hill at the height of the Battle of Britain.

Of the nearly 3,000 pilots who flew in the Battle of Britain, GHQ picked less than 200 of the most outstanding to have their portraits drawn by Captain Cuthbert Orde. John Drummond was among the finest of The Few.

The picture shows John Fraser Drummond with No. 46 Squadron at RAF Digby in late June 1940. At just 21 years old he had already seen action in Norway for which he was to be awarded a DFC and was about to participate in the Battle of Britain, a conflict that four months later would take his life.

I’ve driven past Thornton Garden of Rest many, many times as it’s on my route to Anfield but I’ve only had one occasion to go through the black iron gates. That was for my first experience of bereavement when my granddad was cremated there in October 1992. So it was with a slight sense of unease that I drove through those gates looking for the graves of two of The Few, Kenneth Macleod Gillies and John Fraser Drummond.

Thornton itself is in the Borough of Crosby, roughly seven miles north of Liverpool city centre but only six miles from my home. It’s hard to believe that I’ve lived so close to two of The Few all my life. A picture of John Drummond’s grave in the book The Battle of Britain Then and Now, taken in the late 1970s, shows the base apparently covered with green glass chippings. Right now the grave is in need of some repair.

I pulled up weeds and grass then stepped back to read the inscription on the headstone. Under the RAF brevet it says,

IN LOVING MEMORY OF

F/O JOHN FRASER DRUMMOND

R.A.F. D.F.C.

BORN 19 OCT 1918, KILLED IN ACTION IN THE

BATTLE OF BRITAIN 10 OCT.1940.

“HE FLEW THROUGH WINGED DEATH

TO REACH THE SKIES”

ALSO HIS FATHER

WILLIAM HASTINGS DRUMMOND

DIED 24. SEPT 1967.

John was killed in action just nine days before his 22nd birthday. The reality of just how young the Fighter Boys of 1940 were hit me hard so I decided then and there to make John Fraser Drummond DFC the first of The Merseyside Few I would write about.

First Contact

It’s a mild Sunday morning in October 2009 and I’ve just parked my car in Warbreck Road, Walton. I cross over at the traffic lights and head down Moss Lane. Orrell Park train station is on my left as I start looking for number 70. The road bends round to the left and it’s clear number 70 is a little further than I thought. There’s a mixture of houses along the way and I wonder if this is a result of bombing by the Luftwaffe in the Blitz of August and September 1940. How ironic that John was fighting the Luftwaffe himself at that time.

I arrive at number 70 which was the maternity home where John Fraser Drummond was born on 19 October 1918. It’s in the middle of a row of two up two down terraces. If the Luftwaffe had hit Moss Lane, they had missed John’s birthplace. The premises are now an outlet of Sayers The Bakers, the largest independent pasty retailer in the north-west of England, established in Liverpool in 1912. Sadly it was closed. But now I know John Drummond’s connection to Liverpool. He was born here.

While walking back towards my car it occurs to me that I must be following the route John’s father, William Hastings Drummond, did almost exactly 90 years ago, when he headed back to the Drummond family home, the proud father of a healthy son. I arrive outside 47 Warbreck Road and pause for a few moments reflection. If it’s the original building, it’s the first of the larger semi detached houses in the road. So, who were the Drummonds and how did John become a decorated fighter pilot at the age of 21?

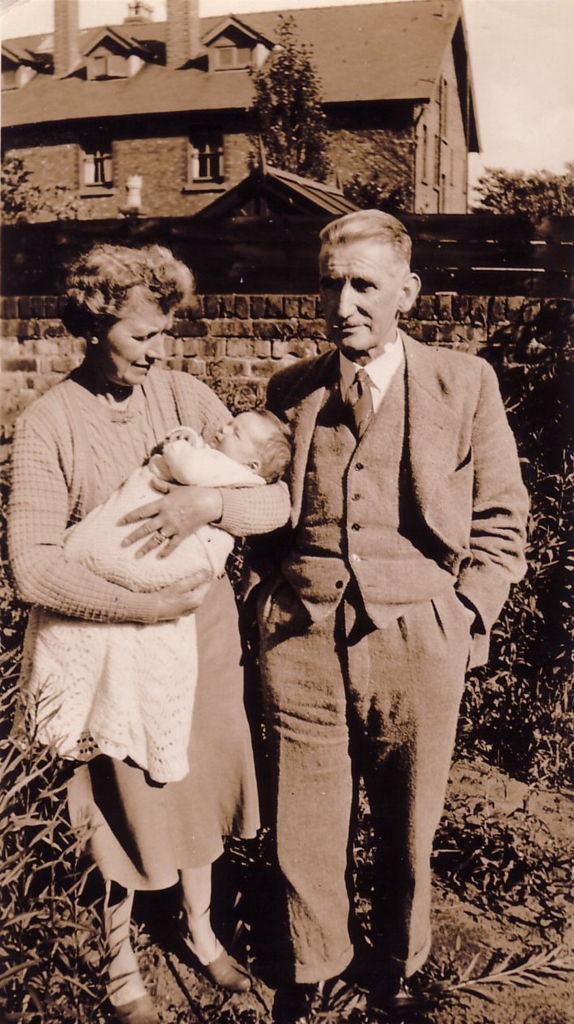

Parents – William Hastings and Nellie Drummond

William Hastings Drummond was born on 27 June 1891 at 46 Wadham Road, Bootle [Google map]. His parents were William Sinclair Drummond, a Scotsman whose career as a marine engineer had brought him to Liverpool, and Jane Drummond. He was the eldest of three brothers, the others being Harold and Robert Drummond.

Like most young men of his generation, William was cast in the shadow of the looming Great War. He volunteered for military service as soon as the war began, joining the ranks of 10th (Scottish) Batallion King’s Liverpool Regiment on 7 August 1914. He was posted to D Company, serving at King’s Park Camp in Edinburgh and Tunbridge Wells billets. He volunteered for foreign service on 27 October 1914.

On 1 November 1914 aged just 23, Private 3179 Drummond embarked on the SS Maidan for France as part of the first territorial battalions to be deployed there. The fighting appears to have taken a considerable toll on him. The family recount that he was completely healthy when he went to war, but after seven months he returned home on 15 June 1915, the day before his regiment fought in The Battle of Hooge. The army had decreed that heart trouble and ‘neurasthenia’ – a now disused diagnosis common in WW1 for people suffering stress, anxiety and depression – and this left him unfit to fight.

He continued to work for the regiment and was promoted to Sergeant in September 1917. He was granted a medical discharge on 1 February 1919 and was awarded the 1914 Star, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal and an annual pension of 11 shillings. He was able to return to his old job at Vincent Murphy and Co Ltd the timber merchants with whom he would stay with all his working life.

John’s mother, Nellie, was born in Huddersfield, Yorkshire to John and Martha Chambers in 1895. The Chambers family moved to Litherland around 1901 where John worked as a commercial clerk and then as a clerk for a wholesale grocers.

William married Nellie Chambers in the summer of 1916 and they went on to have two children, Helen and John. In 1924 they left their home in Warbreck Road moving to 34 Cavendish Road, Blundellsands [Google map]. As William’s career progressed, they were able to move again and in 1930 settled in the house that would remain the family home until William’s death in 1967 at 4 Far Moss Road, Blundellsands [Google map].

William had a successful career eventually becoming co- Managing Director of Vincent Murphy and Co Ltd and travelled the world in the course of his business. He became president of the Liverpool Timber Trade Benevolent Society and was also a Freemason, joining Sylvanus Lodge No 3670 (Bootle) where he became a Worshipful Master.

William died at a nursing home on 27 September 1967. His funeral was held on 2 October at St Michael’s Church, Blundellands, the same church where John’s funeral had been held 27 years earlier. He was interred in John’s grave and his name can be seen on the left hand corner of the grave plot as well as on the headstone.

After William’s death Garda was sold to a Mr R M Faulds and Nellie moved to a nursing home on the Wirral where she was visited daily by her daughter Helen. Nellie passed in November 1968 and was interred in the same grave as John and William although her name doesn’t appear on the headstone.

Harold Drummond

William wasn’t the only member of the Drummond family to see service in the Great War. His younger brother Harold also joined 10th (Scottish) Batallion King’s Liverpool Regiment in October 1915. He was wounded in action on 21 September 1917, reportedly taking a gunshot wound to the face. Five days later he returned to the United Kingdom and became a musketry instructor for the Regiment. He was discharged in 1919 having served for a year and four months with the British Expeditionary Force and was awarded The Silver War Badge, given to service personnel who had been honourably discharged due to wounds, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

However, when Harold spoke of his war experiences, he always insisted that the wounds he received were caused by shrapnel from a bomb exploding in a trench close by to him. The debris from the blast buried him and upon his return to Liverpool he could not sleep indoors, and it took many years for him to overcome his fear of enclosed spaces and sleep again in a bed.

On 17th January 1939 one of Harold’s sons, Ian Sinclair Drummond, died of meningitis pneumonia, just a day before he turned 18. That began the series of tragedies that was to befall them over the next 18 months.

Robert Fraser Drummond

William’s other brother, Robert Fraser (Bert) Drummond, enlisted as a Territorial in the University Section of the Cheshire Brigade Company of the Army Service Corps. He was subsequently commissioned in the Cheshire Regiment serving in France from September 1917 with both the 3rd and 15th battalions, gaining the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. His Service Record read “A reliable officer who has done very good work with this battalion during the severe fighting of the last year,” and was signed by Harrison Johnston on 30th November 1918.

Early Life

John was born at 70 Moss Lane, Liverpool [Google map] on 19 October 1918 in a nursing home run by a midwife, Bertha Tyson.

He was the second child of William and Nellie Drummond who already had a daughter, Helen, born in June 1917. John spent his earliest years at 47 Warbreck Road before the family moved to 34 Cavendish Road, Blundellsands in 1924. He attended a Church of England Primary School near to his home but the family moved again to 4 Far Moss Road in 1930. The family would stay here until John’s father’s death in 1967.

At the age of eleven he attended Deytheur Grammar School, as a boarder, in the small Welsh village of Llansantffraid, Powys [Google map], close to the English border. The school was closed in 1967 and most of it demolished in 1971 but the old school house remains and is now a 750k private residence.

In January 1934 John started Wellington School, Somerset, again as a boarder. He was placed in Willows House and went on to represent them at tennis, cricket and cross country. He took part in the school’s Officer Training Corps, earning his A Certificate in March 1935 before becoming a Lance Corporal in May. He was quickly promoted to Corporal before finishing as a Sergeant. In July 1935 he passed his School Certificates in scripture, English, geography, elementary maths and chemistry. He left Wellington in April 1936 with the Senior Prize for divinity. In 2004 The Battle of Britain Historical Society presented a plaque to Wellington School, recognising John’s achievements as a pilot.

Upon returning to Liverpool, John took up an apprenticeship with Vincent Murphy & Co Ltd of Derby Road, Bootle, the timber merchant his father worked for as a salesman. This work didn’t satisfy John and, influenced by a family holiday to Germany circa 1936 from which he believed the Germans were preparing for war and not wanting to fight in the trenches as his father and uncles had, he was determined to pursue his ambition to fly. So his parents relented and he applied to join the RAF. He passed his medical on 18 November 1937.

John began his training at The Civil Flying School at Hatfield on 4 April 1938 before moving to RAF 5 FTS at Sealand, Flintshire in June. The London Gazette of 24 June confirmed that John had been granted a short service commission as an Acting Pilot Officer on probation with effect from 4 June 1938.

Some of his peers who were also granted short service commissions that day went on to fly in The Battle of Britain;

Maurice Brown (611 and 41 Squadrons)

Aston Cooper-Key (46 Squadron)

John Cutts (222 Squadron)

William David (87 and 213 Squadrons)

Noel Francis (247 Squadron)

Maurice Kinder (85, 607 and 92 Squadrons)

James O’Meara (64 and 72 Squadrons)

Donald Smith (616 Squadron)

John Strang (253 Squadron)

Hugh Tamblyn (141 and 242 Squadron)

John Waddingham (141 Squadron)

46 Squadron

After completing his flying training he joined 46 Squadron at Digby, Lincolnshire on 14 January 1939. Originally equipped with Gloster Gauntlet Mk II single seater bi-plane fighters, the squadron was re-equipped with Hawker Hurricanes in February 1939. They were to see action just 6 weeks after the outbreak of World War II when, on 21 October 1939, Squadron Leader PR Barwell and Pilot Officer RP Plummer attacked a formation of twelve Heinkel 115s five miles east of Spurn Head, shooting 3 down and damaging another.

As a result of this action King George visited Digby on 2 November to compliment the Squadron on the role they had played in protecting coastal shipping from enemy action. He spent around ten minutes with the pilots, including John. The next six months though were uneventful, consisting in the main of providing air cover for the shipping convoys steaming along the east coast. There followed a brief move to Acklington, on the Northumbrian coast, from December to mid January 1940 where John carried out anti-aircraft co-operation flights, playing the part of enemy planes so coastal guns would be practiced and ready for the inevitable raids.

The Norway Campaign

In May 1940, the squadron was selected to form part of the Expeditionary Force in Norway, which had been invaded by the Germans on 9 April. Their Hurricanes were embarked on HMS Glorious and arrived 40 miles off the Norwegian coast on 26 May. The Hurricanes had to take off from the deck of Glorious but as the sea was flat and calm there were doubts that they could do so. Air Ministry figures suggested a 30 knot wind was necessary. The ship’s engineers managed to get HMS Glorious up to a speed of 30 knots so enabling all 18 Hurricanes to take off successfully. 46 Squadron assembled at Bardufoss in the far north of the country [Google map] and began operations on 27 May.

John saw action shortly after his arrival when, on 29 May, he took off from Bardufoss in Hurricane L1794. He sighted four enemy aircraft at 12,000 feet south of Narvik and moved into attack the nearest, a Heinkel 111. Although John hit the starboard engine he had been hit by return fire causing his cockpit to fill with smoke. He turned to go back to Bardufoss but his engine failed. He had no choice but to bale out. He landed in the near freezing waters of Ofotfjord and was picked up by HMS Firedrake, an F-Class destroyer later to take part in The Battle of the Atlantic. John Drummond had scored his first solo kill, a He111 of 2/Kampfgeschwader 26.

Four days later, in the early afternoon of 2 June, John took off in Hurricane W2543, with Sgt Taylor, for a routine patrol over Narvik. An hour or so into the sortie he spotted two Junkers JU 87s attacking a destroyer in Ofotfjord. He went after the first firing around five six second bursts. Smoke coming from the starboard mainplane confirmed he had scored a hit. John watched as it force landed, bursting into flames.

The 7 June was certainly John’s busiest day during his time in Norway. It was also the day he cheated death by an inch, and earned his Distinguished Flying Cross.

He was in the air at 0400 hours patrolling the Narvik area when he spotted three He111s flying in formation. He attacked the first plane but it disappeared into a cloud, so he attacked the other two, hitting the starboard Heinkel. The other one attacked his Hurricane causing him to seek cover in a cloud. On emerging from his cover John saw the damaged Heinkel heading towards the border with neutral Sweden, and so John returned to Bardufoss claiming this as a victory.

After some rest John was in the air again at 1715hrs patrolling Narvik with Flight Officer Mee. They sighted four He111s at around 10,000 feet. Mee attacked the port enemy aircraft and John the starboard. John hit his target causing it to turn for cloud cover. John left it there and went after another of the He111s. Spotting two he attacked one, hitting the rear gun but was hit himself by the other one. A shell pierced his windscreen, clipping his goggles and helmet before ricocheting out of the cockpit hood, making a large hole in the process. John returned fire again but lost the enemy planes in cloud. He claimed one victory and two damaged.

On landing John learnt that Operation Alphabet had been activated and the squadron had been ordered to evacuate Norway immediately. They had to fly their Hurricanes back to HMS Glorious. Perhaps because of the day he had had – two sorties in fourteen hours – John was not chosen for this task. Instead he went with ground crew of 46 Squadron on the SS Arandora Star. [For more about the fate of the SS Arandora Star, see the Additional page]

At 0300 on 8 June HMS Glorious was detached with the destroyers Ardent and Acasta to head for Scapa Flow while the other carrier, HMS Ark Royal, and the rest of the fleet remained behind to escort the slower main convoy. At 1545 the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau spotted Glorious and opened fire directly hitting her bridge. Glorious returned fire but was hopelessly outgunned. By 1720 she was dead on the water and sinking fast. She took with her eight 46 Squadron pilots and their Hurricanes. John Drummond disembarked at Gourock on 13 June and returned to Digby the next day.

His overall score in Norway was four victories and two damaged enemy aircraft for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.The citation in the London Gazette of 26 July 1940 read,

The KING has been graciously pleased to

approve the undermentioned awards, in recognition

of gallantry displayed in flying operations

against the enemy:—

Awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Pilot Officer John Fraser DRUMMOND (40810).

During operations in Norway, this officer

shot down two enemy aircraft and seriously

damaged a further three. On one occasion,

as pilot of one of two Hurricanes which

attacked four Heinkel 1ll’s, he damaged

one of the enemy aircraft and then engaged

two of the others. Despite heavy return

fire, Pilot Officer Drummond pressed home

his attack, silenced the rear guns of both

aircraft and compelled the Heinkels to break

off the engagement.

The Squadron re-formed at Digby becoming operational at the end of June.

The next two months consisted of convoy and defensive patrols. John was posted to RAF 7 Operational Training Unit at Hawarden where he taught Czech and Polish pilots the rudiments of combat flying in Spitfires. He was briefly posted back to 46 Squadron where, amongst other duties, he was chosen to lead a flight of three aircraft escorting The Lord Lloyd, Secretary of State for The Colonies, from North Coates to Hendon.

On 5 September he was plunged right into the thick of the Battle of Britain when he was posted to 92 Squadron, first at Pembery then at Biggin Hill.

92 Squadron was already an effective fighter unit thanks largely to its leadership and the strength of character of its pilots. It also had a reputation for indiscipline, having a second home at the White Hart pub not too far from Biggin Hill in the small village of Brasted.

From 1st January 1940 it had been led by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell until he was shot down and captured on 23 May. He would later be executed by the SS for masterminding the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III. Other notables in the squadron included Paddy Green, Bob Stanford-Tuck, Brian Kingcome, Tony Bartley, Johnny Kent, Allan Wright, Don Kingaby and Geoffrey Wellum.

On 6 September John made his first flight with 92 Squadron and on 8 September he departed Pembery for Biggin Hill. On his arrival here he roomed with Geoffrey Wellum who wrote in his memoirs, First Light,

“I share a room with a new pilot. His name is John Drummond. He was waiting at Biggin when we arrived, a quiet retiring sort of chap, a bit of an introvert. As we unpack our kit I get to know a little about him, although he doesn’t volunteer an awful lot. It appears he was in a Gladiator Squadron in Norway and they were, of course, hopelessly outnumbered and virtually decimated. He has a DFC but obviously doesn’t want to talk about it so I don’t press him. We get on well enough. He’s friendly so the arrangement suits me, not that I’m in a position to object. Hardly know he’s around anyway.”

So the last 35 days of John’s life were about to be played out defending his country against the imminent threat of invasion.

His first action in the Battle of Britain came in the late afternoon of 9 September when 92 Squadron was scrambled to defend Biggin Hill itself. They lost two aircraft but fortunately no pilots.

On 10 September John was ordered to fly to Hawkinge as part of an escort for an Avro Anson that was ‘spotting’ the results from a new 14 inch gun firing shells across the English Channel. This proved to be an uneventful flight and he returned to Biggin Hill in the early evening.

On 11 September, after some hours of much needed rest, thirteen aircraft of 92 Squadron were scrambled at 1520 hours to intercept a large formation of bombers, escorted by fighters, over Dungeness. John was flying as number 3 of Green Section. The squadron split up over Maidstone as pilots carried out individual attacks.

John encountered three Messerschmitt Bf109s at 20,000 feet, attacked number three firing a few short bursts before breaking away. He spotted a Hurricane being attacked and hit its assailant hard as it broke away. He pursued it, finishing off his ammunition in the process and causing white smoke to pour from its tail. John looked round to see two of the Bf109s diving on his tail so did a half roll and dived sharply to shake them off before heading back to base, landing at about 1730 hours. When reporting to Squadron Intelligence Officer Tom Wiese, John claimed the Bf109 as a probable.

92 were kept busy over the next few days defending Biggin Hill but rain, cloud and unsettled weather hampered enemy action to a large degree. The RAF aircraft took some punishment but fortunately the pilots were relatively unscathed. The action escalated on 18 September when 92 were scrambled to meet the third major attack of the day. At 1555 hours John flew one of eight Spitfires ordered off from Biggin Hill to rendezvous with 66 Squadron over base. Cloud cover forced them down to 18,000 feet where they sighted a formation of sixteen Bf109s heading toward Rochester. The Squadron went in to attack but the enemy aircraft simply headed for the cloud cover above. Despite losing sight of the Bf109s, Squadron Leader Kingcome managed to collect three pilots and attacked a formation of eighteen Ju88s and a He111. By the time the Spitfires returned to base they had claimed one and a half Ju88s destroyed and two He111s as a probable and damaged.

Showery weather on 19 September contributed to a day of relative inactivity so John and 92 were not called into action. That night the Luftwaffe dropped heavy explosive and incendiary bombs over a wide area of Liverpool, starting their campaign to destroy the city, a campaign that would soon have devastating consequences for John’s family.

On the morning of 20 September, 92 were scrambled to meet the one major attack of the day. A force of a hundred enemy aircraft was intercepted over east Kent, apparantly on course for London. In the ensuing melee two Spitfires of 92 were shot down (Sgt PR Eyles and P/O HP Hill both killed) by leading Luftwaffe ace Major Werner Molders (Kommodore of Jagdgeschwader 51) near Dungeness. These victories took his tally to forty making him the first fighter pilot to reach this total during the war.

Saturday 21 September was a quiet day for John and 92 as they were only involved in fighter sweeps over east Kent. There was little combat and only one enemy aircraft was reported damaged. That evening, however, the Luftwaffe stepped up their assault on Liverpool with the heaviest raid yet. One bomb smashed into the front of 63 Worcester Road, killing John’s grandmother and aunt where they slept.

[For more about the bombing of the Drummond house, see the Additional page]

It’s not clear when on 22 September John received the news from Liverpool, but it was perhaps fortunate he was only required to fly a short patrol over Beachy Head as fog and rain reduced activity to a minimum.

By the next morning the weather had cleared up enough for the Germans to launch their first major attack of the day at 0930 hours and John, flying Spitfire QJ-T (X4422), and 92 were scrambled to meet them. John climbed to 20,000 feet then was ordered by Flight Lieutenant Kingcome to attack any Bf109s he saw. Very quickly he got on the tail of one that was attacking another Spitfire, that of Tony Bartley. He fired a short burst that caused clouds of white smoke to pour from the exhaust. The pilot of the Bf109, Feldwebel Kuppa of 8/Jagdgeschwader 26, took evasive action but John followed him down firing short bursts until it became apparent that Kuppa would have to make a forced landing. He ended up in a pond near Grain Fort on the Isle of Grain but was captured unhurt. John returned to Biggin claiming it as a victory.

John’s Spitfire that day, X4422, was shot down by Bf109s three days later over Farningham, killing its pilot, 20 year old Flt/Lt Jimmy Paterson.

On 24 September the Germans again decided to make their first major attack of the day an early one. John, flying as Blue 1, and 92 were scrambled at 0845 hours, joining up with 66 and 72 Squadrons over the Thames Estuary. At 16,000 feet they spotted a formation of Ju88s escorted by a large number of Bf109s. John led Blue Section through the escort and attacked the bombers. In his combat report John described carrying out a beam attack on the rear Ju88, hitting the port engine.

After breaking away from the bomber John realised he had three Bf109s on his tail. He turned onto the tail of the rear Bf109, firing a five second burst. Clouds of white smoke pouring from its exhausts confirmed he had damaged it. He turned on the second Bf109, again firing short bursts and claimed to have damaged that. On his return to Biggin John declared he had expended 2,000 rounds and claimed an Bf109 as a probable, one damaged and a Ju88 damaged.

It’ll never be known how John felt about missing the funeral of his grandmother and aunt that took place on 25 September and the effect it had on him, but due to decreased enemy action in the London area, he didn’t fly again until 27 September. At 0915 hours he was ordered to patrol base as Yellow 1 flying Spitfire QJ-G (X4330), taking two other aircraft him. They engaged by enemy fighters and John damaged an Bf110. He was credited with a third of a victory as it was attacked by Hurricanes, most likely of 46 Squadron, on its way to crash landing in a field just south of Westerham.

After lunch in dispersal the squadron was scrambled at 1530 hours. John was again flying as Yellow 1. They intercepted a formation of Ju88s over Sevenoaks and John attacked the outside aircraft at the rear of the formation. The Ju88s engine was already smoking when another Spitfire from Yellow Section also hit it. It crashed near High Halden railway station.

Records indicate that 92 were not in action again until 30 September. At 1700 hours and still flying as Yellow 1, John was on patrol at 27,000 feet north west of Brighton when he spotted a formation of 15 bombers escorted by around 50 fighters 10,000 feet below. John dived towards the bombers and encountered two Bf109s on the way down. After firing a four second burst at a distance of 350 yards, John saw smoke coming from the Bf109 and it began to lose height. He watched it descend towards Beachy Head before returning to Biggin Hill. John claimed this as a probable.

With the coming of October, the Battle of Britain entered its final stage and John was next in action on the morning of 5 October. He took off about 10 minutes after the Squadron as Ganic 17 and set about finding them. Over Dungeness he saw 12 Bf109s and decided to carry out a solo attack. He fired on the rear fighter, hit it then watched it do a half roll before crashing in the sea. This is likely to have been a fighter from 2/JG 77. Having just seen the Bf109 hit the sea, John spotted a Henschel Hs126 flying low above the water. In his characteristic tenacious style he followed and engaged it, finally bringing it down just two miles from the French coast. He couldn’t know it, but the Henschel was to be his last victory.

The day was further marked by official RAF artist Captain Cuthbert Orde meeting John shortly after he landed and drawing his portrait. Of the nearly 3,000 pilots who flew in the Battle of Britain, GHQ picked less than 200 of the most outstanding for this accolade.

Orde’s iconic pictures of The Few are always striking. That John’s was drawn now, an hour or two after his final kill and with only five days to live, is all the more poignant.

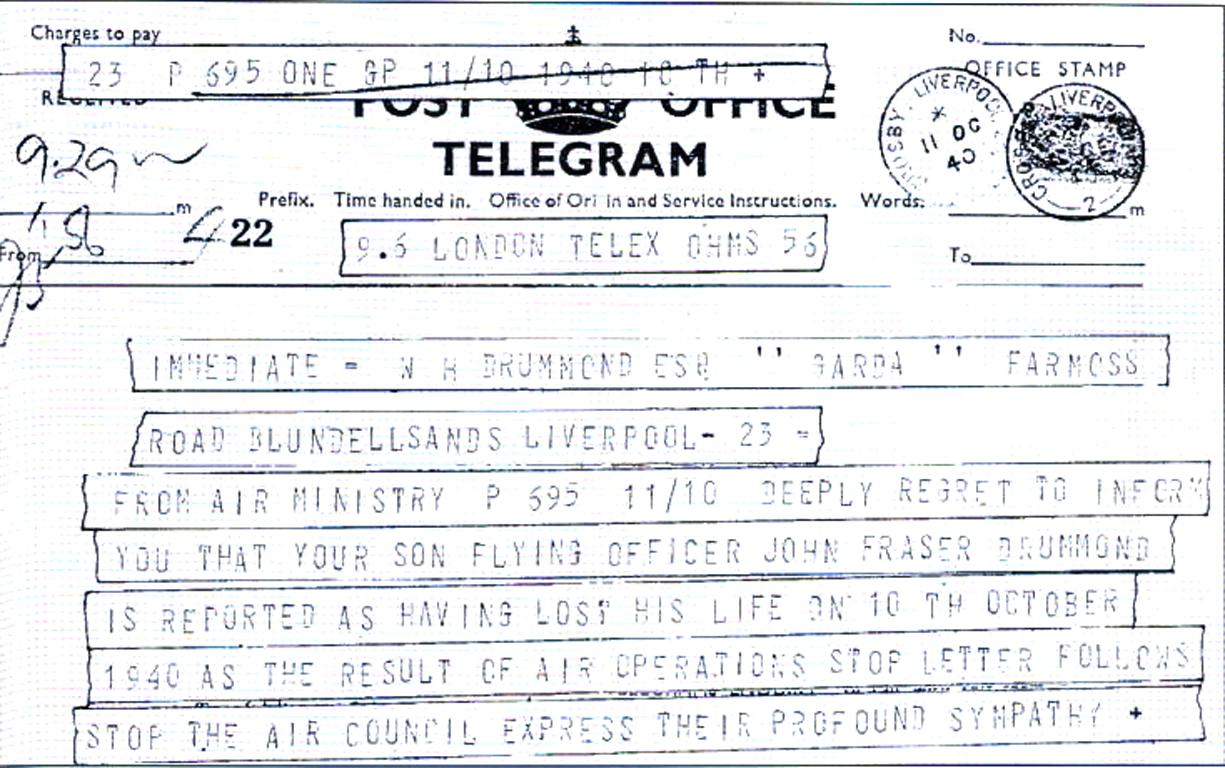

Death

John awoke on Thursday 10 October to find the weather showery but bright. No doubt he would see action again today. Since the deaths of his grandmother and aunt John had flown almost continuously, claiming four victories, two probables, two damaged and one shared. He had also seen four colleagues killed in action.

At 0710 hours, he took off in Spitfire QJ-X with the rest of squadron to patrol Maidstone. After 40 uneventful minutes they were vectored onto a Dornier 17 just east of Brighton. All nine Spitfires descended on the enemy aircraft but experienced real difficulty in firing as their windscreens were iced up meaning the deflector sights could not be used. Two of the Spitfires got in close, fired some bursts and got out. The Dornier flew on.

John and Pilot Officer Bill Williams both attempted beam attacks from either side of the Dornier. They missed and continued turning blindly towards each other. Their Spitfires touched, the starboard wing of John’s machine striking the tail of Williams’. John had to bale out but did so too low for his parachute to open. He was still alive after hitting the ground so a priest was able to administer the last rites before John died in his arms. His Spitfire crashed close to him, landing on a flintstone wall that bordered Jubilee Field and St Mary’s Convent in Portslade [Google map].

When his body was examined, John was found to have been wounded in his left arm and leg. Bill Williams, it later transpired, had been shot through the head so was already dead when their machines collided.

Censorship meant John’s death was noted in the vaguest of terms in the next days Brighton Evening Argus. It simply said, ‘Our losses yesterday were five aircraft but the pilots of two are safe’.

Funeral

John Fraser Drummond’s funeral took place at St Michael’s church, Blundellsands, on Tuesday 15 October 1940. The service was attended by the Mayor of Crosby among other local dignitaries and the chosen hymn sung was Abide With Me. He was buried in Thornton Garden of Rest just four days before his 22nd birthday. His short life had only known childhood, school, barely a year at the timber merchants and less than three years in the RAF.

Today, the first thing that strikes you about the grave is its size and grandeur. It’s a ten foot square kerbed memorial with a stone flower container at its foot and three pointed stones at intervals along each side. The headstone has two grey granite pillars either side of the inscription. The twelve concrete flags which form its base are visible but clearly the passing of time has taken its toll as they are very uneven with grass and weeds growing between the cracks. There are some green glass stones scattered across the grave but not nearly enough to cover it.

John Drummond was the third person to be interred in Thornton Garden of Rest [Google map]. It stands in Lydiate Lane, built on a site purchased from the Earl of Sefton in 1936, and owned by the Crosby, Litherland and Waterloo Joint Burial Board. It was opened, consecrated and dedicated by Dr AA David, the Lord Bishop of Liverpool, on 23 July 1940.

John’s final resting place is Grave 3 in Section A. There are photocopies of the layout of the Garden available on entry. It is in a plot next to the crematorium and on the right as you advance down the driveway.

Germany Calling

John’s death did not go unnoticed in Germany. During his nightly radio broadcast Lord Haw Haw had this to say about the action that took John’s life: “A single reconnaissance aircraft, returning from photographing the holocaust of London, was attacked today by six Spitfires. Its gallant crew showed great courage in destroying three. The aircraft crashed in France but the photographs have been saved”.

Memorials

John is commemorated in several places.

As well as having his name engraved on The Battle of Britain Monument in London and The Battle of Britain Memorial at Capel-le-Ferne, John’s name is engraved on two memorials in Crosby. There is one inside St Michaels Church where his funeral was held, and one in Alexandra Park.

He is also recorded in the Book of Remembrance, the casualties list and on the Roll of Honour in St Georges Chapel at Biggin Hill.

He is listed in the Book of Remembrance at St Clement Danes, the RAF church in London.

There is also a plaque at Wellington School commemorating John Drummond and another old old boy who flew on the Battle of Britain, Edward Graham.

The Drummond Family in the Blitz

It was during the first phase of bombing that became known as the Blitz that tragedy first struck the Drummond family. At 1932 hours on Saturday 21 September 1940 an air raid warning signalled that the Germans had launched another raid against Merseyside.

The first raids of the Blitz had occurred on 29 August 1940 and they had been almost continual since then. Though much worse was to come, on this night Liverpool endured its worst air raid since the war began. The Luftwaffe unleashed a fearsome barrage of incendiary bombs on densely populated residential areas. As the residents, Air Raid Patrol wardens and Auxiliary Fire Service tried to put the fires out, a second wave of bombers passed overhead dropping heavy calibre high explosive bombs.

At 63 Worcester Road Bootle [Google map], John’s grandmother, Mary Drummond, and his auntie Edith Drummond were in bed in a ground floor room. As they lay there in the small hours of 22 September, a bomb smashed into the front of the house. The two women had no chance and were killed where they slept.

Another of John’s relatives, Mary Lang (known as Aunty Polly in the family, who was both deaf and nearly blind), who was asleep in the back of the house, miraculously survived. When the all clear sounded at 0421 hours the next morning the clearing up began.

The Bootle Times of Friday 27 September 1940 carried on its front page the news of the deaths of Mary and Edith Drummond. On the inside of the same edition it reported on their funeral. It took place on Wednesday 25 September, leaving from John’s uncle Bert’s house at 9 Worcester Road and taking place at Christ Church in Bootle, a few hundred yards away from the scene of the tragedy that still lay strewn with rubble.

The Chief Mourners that day were Mary’s sons William (John’s father), Bert and Harold, her brother G Hamilton, grandson WF Drummond, granddaughter Helen Drummond, nephew J Gibbons and nieces Mrs Nutall and Mrs Salisbury. John’s parents sent a floral tribute on behalf of the family.

They were interred at Bootle Cemetery in the same grave as John’s great grandfather William Sinclair Drummond. The inscription on the grave stone read, “..killed by enemy action on 22nd Sep, 1940”.

John was on active duty with 92 Squadron at Biggin Hill so was unable to attend the funeral. He had engaged the enemy the day before, claiming an Me109 as a probable and damaging another along with a Ju88.

Visiting Worcester Road today is a stark reminder of that September night in 1940. The houses were re-built as necessary. All except for number 63, where there is just an empty space.

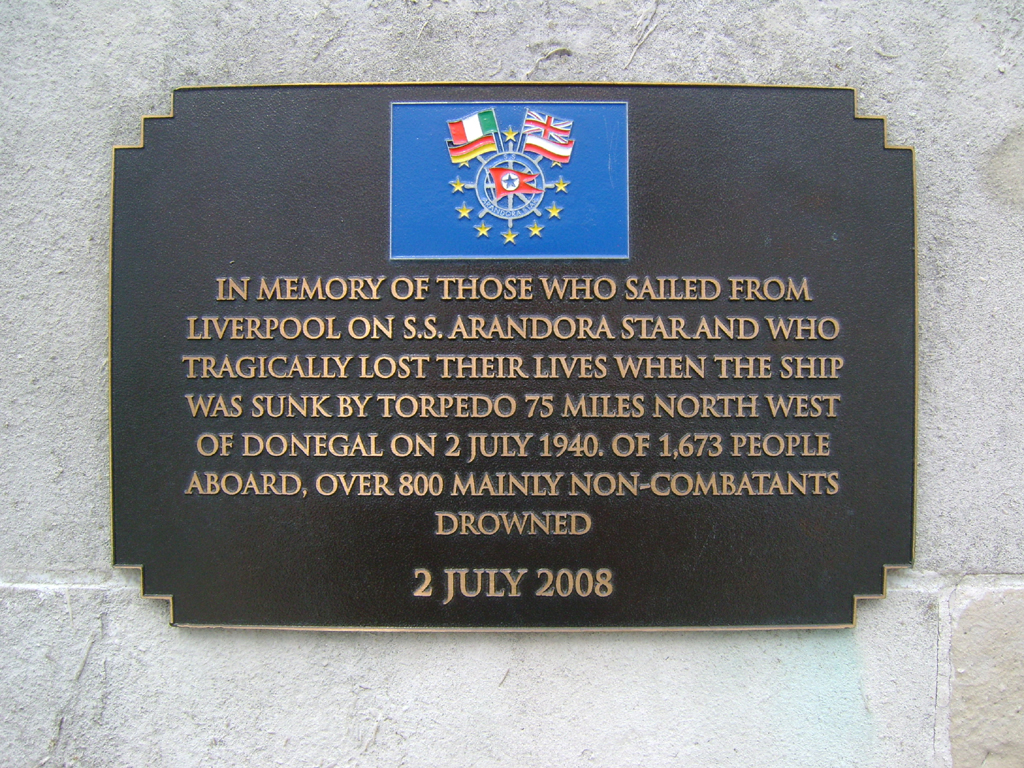

SS Arandora Star

The SS Arandora Star was a British registered cruise ship operated by the Blue Star line from the late 1920s through the 1930s. At the onset of World War II, she was refitted and was assigned as a transport ship. She evacuated servicemen from Norway, including John Drummond, and from France in June 1940 before undertaking what was to be her final voyage transporting Axis nationals and prisoners of war.

On 2 July 1940, across the river from the Cammell Laird yard that built her, she left Liverpool unescorted. She was bound for St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador with nearly 1,200 German and Italian internees who had been detained under harsh rules regarding people from enemy countries.

Almost all were civilians, many of the Italians had been in Britain since the turn of the century and some of the Germans were refugees who had fled Nazi persecution. Only 86 POWs were aboard. There were also 374 British men, comprising both military guards and the ship’s crew.

Although she was not carrying combatants, she did not bear a red cross, and so was easily misidentified as a ship on active service. At 06.58 hours off the northwest coast of Ireland, she was struck by a torpedo from the German submarine U-47, commanded by U-Boat ace Günther Prien. U-47 fired its single damaged torpedo at Arandora Star. All power was lost at once, and thirty five minutes after the torpedo impact, Arandora Star sank. Over eight hundred lives were lost.

There is a plaque bearing her name in front of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board building in Liverpool.

For more comprehensive research on the Arandora Star, see these pages:

SS Arandora Star

Men That Came In With The Sea

The Peoples War

In 1940 the war wasn’t only being fought by courageous young fighter boys in the skies above southern England but by ordinary people in the villages, towns and cities of Great Britain as well. The Home Front.

This was a period when families were separated, often coping with the loss of a loved one. Cities were being bombed, and people had to find new and ingenious ways to keep their lives as normal as possible. One such account of life during these unprecedented times was kept by Brighton school teacher Helen Roust in her diary. Her entry for October 10th, the day John died, reads as follows;

All clear from the night warning at 7am – we were all awake. We heard machine gunning at 8.20am. Time bomb in the Hythe Road district at 12.20, sirens at 2pm, all clear at 2.40. Children have been excitable. Small wonder that we have all felt a little nervy. A spitfire came down on the Fallowfield Estate. Sirens for the night at 7.20.

The Spitfire she refers to is John’s.

Thomas Monks Taylor

In Section A, grave 1 of Thornton Garden of Rest, the same section as both John Drummond’s and Kenneth Gillies’ graves, is the impressive headstone of Pilot Officer Thomas Monks Taylor, killed on 26 July 1940. His inscription reads “One of The Few”.

However, the term ‘The Few’ refers to pilots who flew with fighter squadrons in the Battle of Britain, and Pilot Officer Taylor was not one of them.

There can be no suggestion that his relatives somehow sought some false glory for this brave officer. Instead, it can only be that the precise definition of ‘The Few’ used today was not yet fixed in the public mind.

So, who was he, and why is he recorded as being one of The Few?

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, Pilot Officer Taylor joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. Once hostilities commenced he was called up and later granted a commission as a Pilot Officer. He was posted to 50 Squadron in Bomber Command as an Air Gunner, flying Hampdens from RAF Hatfield Woodhouse in Yorkshire. 50 Squadron saw action in March 1940, when it participated in Bomber Command’s first attack on a German land target – the mine-laying seaplane base at Hornum on the island of Sylt [Google map]. It’s likely Pilot Officer Taylor participated in this mission.

Although Pilot Officer Taylor flew operationally during the Battle of Britain period, he did so with Bomber Command rather than Fighter Command. Churchill’s speech that coined the term The Few commended those who had fought to defend Britain that summer. Pilot Officer Taylor had been attacking Germany.

This author pays the greatest of respect to Pilot Officer Taylor and thanks him for the service he gave in helping to defeat Nazi Germany.

Thomas Monks Taylor’s name is on Crosby’s Alexandra Park war memorial alongside John Drummond’s.

Post Script

Portslade

I visited Portslade in search of John’s crash site. Using Michael Robinson’s description of the crash in his book The Best of The Few, I was looking for St Mary’s Convent, Jubilee Field and a flint wall, all with a church nearby.

Some pre-trip research had revealed that St Mary’s Convent no longer existed but the building and its grounds now belonged to Emmaus Brighton & Hove, a community dedicated to helping the homeless.

I arrived in Portslade early on a very wet Sunday morning. Locating the former St Mary’s Convent was easy enough and finding the church took a matter of minutes as its tower was clearly visible through the grey drizzle. It turned out to be St Nicholas Church.

I couldn’t see a nearby field or a flint wall so took a chance and asked a passer by. He explained that Jubilee Field had been built on and was now Easthill Drive [Google map]. He asked why I was interested and, after I explained, said that he had personally witnessed John’s crash as a boy and even cycled up to Jubilee Field to see the wreck of the Spitfire.

I was too stunned to react sensibly and the gentleman wanted to get out of the rain and into church. Quickly I ran onto the High Street and bought a pen and paper, wrote my contact details down and rushed back to the church. The service had just started so I couldn’t interrupt. I whispered my tale to a lady dishing out hymn books and she agreed to pass my details on to the gentleman I spoke to.

That done, I decided to sneak into the grounds of the former Convent and see if there was any sign of a flint wall. There was indeed a flint wall dividing the grounds from the back gardens of the houses in Easthill Drive. I walked along the length of it and estimated where John may have come to ground, then took a walk up Easthill Drive.

A couple of days later I received a call from the gentleman I talked to in Portslade who simply said he didn’t want to remember the crash as it was just too long ago. I pressed him gently but he was adamant. He did though confirm that the flint wall I saw was the original flint wall John’s Spitfire came down on. This is close as I am ever going to get to John’s crash site.

Bert Drummond

In a more personal post script, I discovered that John’s uncle, Bert Drummond, actually lived in my road from 1963 until his death in 1972. His old house is currently up for sale with my brother-in-law’s estate agents.

To add a further personal note to this story, Bert actually taught my father-in-law physics at Bootle Grammar School for Boys during the 1940s. My father-in-law remembers “Bulldog” Drummond well, saying he was a great teacher and an influence on his future career as an engineer. He even played for the Bootle Grammar School Old Boys Association football team set up by Bert.

First Light

Just as I completed my research, I learned that BBC TV were filming a dramatisation of Geoffrey Wellum’s book First Light, and it was to include John Drummond played by Alex Waldmann. The BBC page has some information, with more in their press pack.

Bibliography

Aces High – Christopher Shores and Clive Williams

Aces High Volume 2 – Christopher Shores

The Battle of Britain Then and Now (Fifth Edition) – Winston G Ramsey

Battle Over Britain – Francis K Mason

Best of The Few: 92 Squadron 1939-40 – Michael Robinson

Bootle in the Second World War – Major G Salt

Fighter Boys: Saving Britain 1940 – Patrick Bishop

First Light – Geoffrey Wellum

Men of The Battle of Britain – Ken Wynn

RAF Fighter Squadrons in The Battle of Britain – Anthony Robinson

Additional material:

46 Squadron Combat Reports

46 Squadron Operational Record Book

92 Squadron Combat Reports

The London Gazette, 24 June 1938

The London Gazette, 26 July 1940

Thanks to the following for source materials and assistance:

South Sefton Local History Unit at Crosby Library

Brighton History Centre

National Archives

46 Squadron Association

Wellington School

Laurie Chesters, St Georges Chapel, Biggin Hill

Thanks to Major I.L. Riley TD MA FSA Scot (ret’d), Honorary Secretary, Liverpool Scottish Regimental Museum for research into John’s father and uncle’s WWI record.

Special thanks also to Group Captain Dougie Barr of 46 Squadron for unique material and insight.

Special thanks due to Ulf Larsstuvold for his remarkable analysis of the 46 Squadron photographs that enabled me to place John in Norway to the exact day.

Special thanks to Geoff Wellum for sharing his personal memories of John and allowing me to quote directly from his book First Light.

A particular special thanks to the Drummond family whose input, generosity and encouragement have been invaluable in helping me complete this piece.

Comments are closed